Home

October 27, 2024

I recently spent nine days in the hospital getting a tracheostomy. The surgery was to prevent my death by suffocation. As the cancer at the root of my tongue has grown, the opening of my airway has shrunk and now could be blocked, even by a wad of dried mucus.

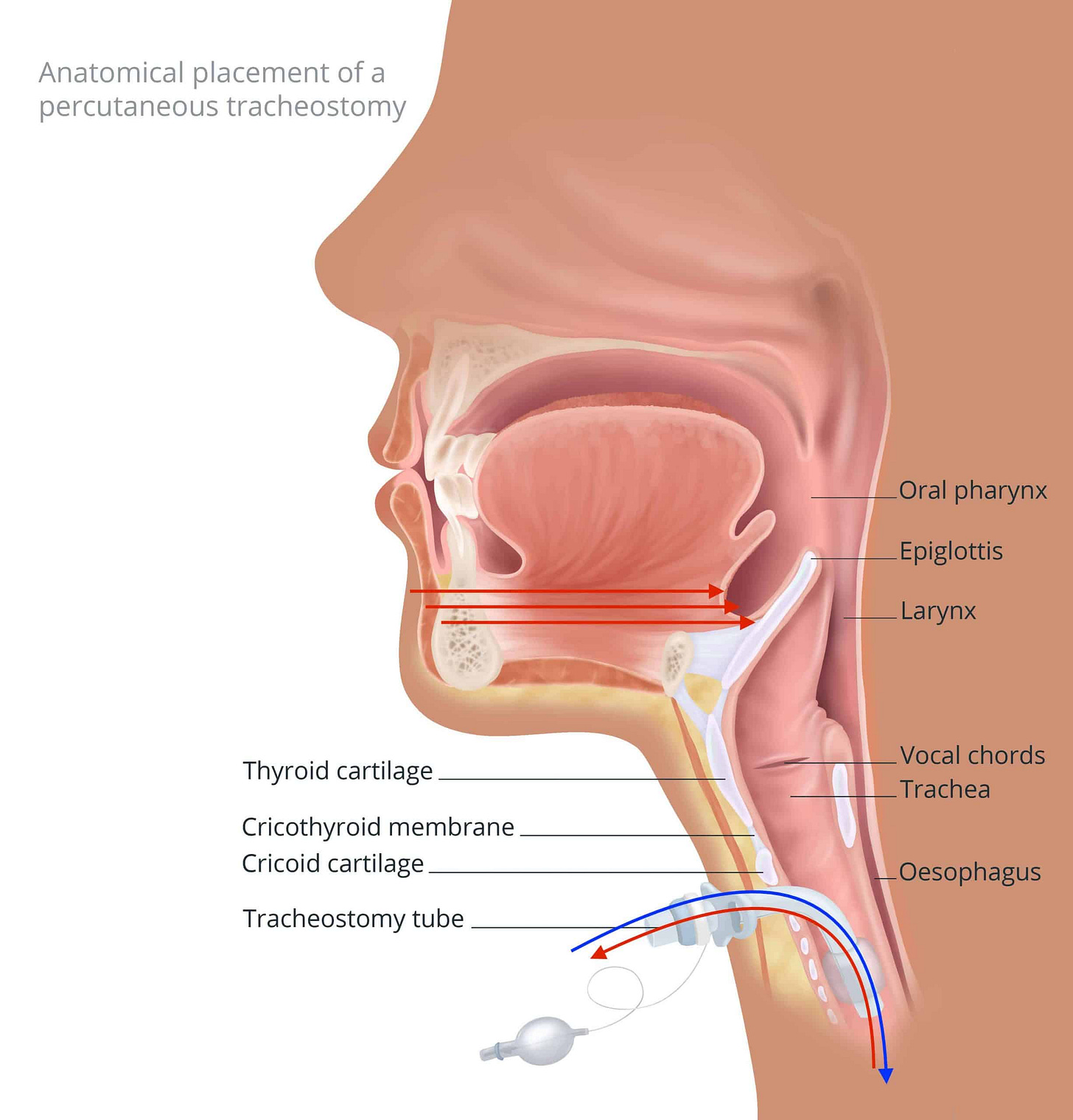

A surgeon cut a hole in my trachea and inserted a collar to keep the hole open. She then put a cannula (a tube) through the collar. One end of the cannula opens to the world, and the other reaches into my windpipe. I now breathe through the cannula. The collar/cannula system is called a tracheostomy or, colloquially, a “trach” (pronounced ‘trayk’).

This operation requires an extended hospital length of stay, in part for recovery from the surgery but also because I must learn how to maintain the trach.

For example, the flesh surrounding the collar can break down and become infected; there’s a technique to keep it clean.

My cancer—or my pneumonia, who knows? —stimulates the production of lots of mucus. This mucus accumulates in the cannula, blocking my ability to breathe. A cough will clear most of this mucus, but this means the mucus shoots out of the cannula and down onto my shirt.

Instead, I insert a long, thin tube into my cannula and suction the accumulated mucus. Once or twice a day, I extract the old cannula and insert a new one through the collar and down my throat.

If maintaining the trach sounds like a tedious chore, it is. However, it is less time-consuming and more effective than coughing up the mucus and spitting it into a paper towel, as was my practice before the tracheostomy. Moreover, the trach reduces the chance that I will die by suffocation. On balance, the trach improved my quality of life.

Now for some hard truth. When the endoscopy showed that the cancer had spread to the epiglottis, it meant that I was getting no measurable benefit from the clinical trial drug.

As a result, the clinical trial director decided that I should no longer receive the experimental immunotherapy. In doing so, he correctly followed standard research ethics. Even though it appears that the experimental drug cannot benefit me, it could still harm me.

I agree with him: I shouldn’t be taking a drug with no apparent benefit and an unknown risk of harm.

More importantly, the experimental drug’s failure means that every evidence-based treatment available to me has failed. There are no further treatment options; we can’t stop this cancer.

Someone might retort, “You can’t know that for certain.” No, I can’t know for sure that no treatment can help. But similarly, that every swan we see is white cannot prove that there are no black swans.

Therefore, I state this without hedging: I have no further hope of getting an extension of life from a cancer treatment or an improvement in quality of life, let alone a cure. I plan to stay at home, receiving care from one of Ontario’s community hospice teams.

I need rest, but you can’t rest in a hospital: too much light and noise. Home can be dark and quiet. Of course, the best part is being with my family and being cared for by them.

But, more of the hard truth is that even at home, it’s not much of a life.

I can’t speak, and I can’t swallow. I breathe through a tube, I pee through a tube, and I eat and drink through a tube. The cancer seems to steal three-quarters of every calorie I consume; I’ve lost another 20 pounds since before the trach. There’s pneumonia that won’t go away, however much antibiotic I feed it. I must suction accumulated saliva from my mouth and infected mucus from my trach. A flight of stairs exhausts me. I cannot describe how weary I am.

Cancer has disabled my participation in what gave me the greatest joy, excepting love: cooking, eating, sex, athletics, science, and travelling the world to see its great paintings. I’m still in a hospital bed; it just happens to be at home.

These circumstances force me to ask myself again: “Why keep living?” I have addressed this question before and stand by my previous answers.

One reason is that I still have a core sentience: I can hear, see, think, read, and write; all extraordinary gifts. The world is horrible and beautiful, but I remain engaged. Moreover, my family and friends want me to live, and I want time with them. I have also argued that in every situation, there are opportunities for small acts of love and kindness that even the sick can give others. We should never despise these small acts; we have no idea about their long-term consequences.

Perhaps a saint could get through my dark times on what I proclaimed above. However, I need more to sustain my life, and I am not alone in this. Jesus himself, in the garden, was wracked by abandonment and terror. As Leah Libresco Sargeant once said,

The world hears [Christianity’s] ‘noes’ more clearly than its ‘yeses.’

I want to help articulate that yes. I believe that by continuing to live, I can contribute by imagining a better future.

Charismatic secular leaders drove the world of my youth, but history demolished them; thank you, Mao Zedong (“first-time tragedy”) and Donald Trump (“second-time farce”). In the wreckage they left, we must move forward peacefully, with faith that a better world is possible, even if we cannot see it.

I see hope only in the Christian future of resurrection and new Creation.

St Paul teaches that,

The gifts [Jesus] gave were that some would be apostles, some prophets, some evangelists, some pastors and teachers, to equip the saints for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ, until all of us come to the unity of the faith and the knowledge of the Son of God, to maturity, to the measure of the full stature of Christ. (Ephesians 4:11-13)

My gift, such as it is, is the ability to write. When I wake up each morning, I must grasp this gift and accept the responsibility it entails. Often, darkness overcomes me. I am grateful that I can recover the light that guides my writing.

They came to Jericho. As he and his disciples and a large crowd were leaving Jericho, Bartimaeus, son of Timaeus, a blind beggar, was sitting by the roadside. When he heard that it was Jesus of Nazareth, he shouted and said, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” Many sternly ordered him to be quiet, but he cried even more loudly, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” Jesus stood still and said, “Call him here.” And they called the blind man, saying, “Take heart; get up, he is calling you.” So, throwing off his cloak, he sprang up and came to Jesus. Then Jesus asked him, “What do you want me to do for you?” The blind man said to him, “My teacher, let me see again.” Jesus told him, “Go; your faith has made you well.” Immediately, he regained his sight and followed him on the way. (Mark 10:46-52)

I am like Bartimaeus, desperate in my illness and often unable to see a path forward. I am grateful when granted faith and light, but my ability to see the light fades and must be restored. To restore it, I return to prayer and scripture.

God willing, I will write about what the new Creation might be like.

Again Bill, I find your willingness and ability to share your thoughts and feelings about your journey through this stage in your life brave. Many people find it difficult to read, I would imagine since dying scares so many. As a retired RN with 41 yrs of full time service under my belt and having often worked with folks in hospice and palliative care, i find your bare honesty poignant. I wish you comfort, love, and many blessings for you and your family.

Bill, my heart is broken, but also filled by your courage. Peace, my friend.